Architecture, Urban Design

The 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games Village created a unique experience for athletes and delivered new housing for East London

The number of Olympic athletes has drastically grown since the first modern Games were held in Athens in 1896, when 280 athletes from 12 countries competed. The 23,200 athletes and officials attending the London 2012 Olympics and Paralympics reveal the growth in participation in this global event.

For London 2012, this translated into beds for 16,000 athletes and team officials during the Olympic Games and 7,200 for the Paralympic Games. When the host city is also accommodating in excess of 500,000 overseas visitors, a dedicated Athlete’s Village is essential.

The winning bid from London for the 2012 Summer Games was grounded in the development of a new Olympic Park and residential quarter in Stratford, East London. This located the athletes inside the central Olympic zone, walking distance from the major venues and close to other venues and transport.

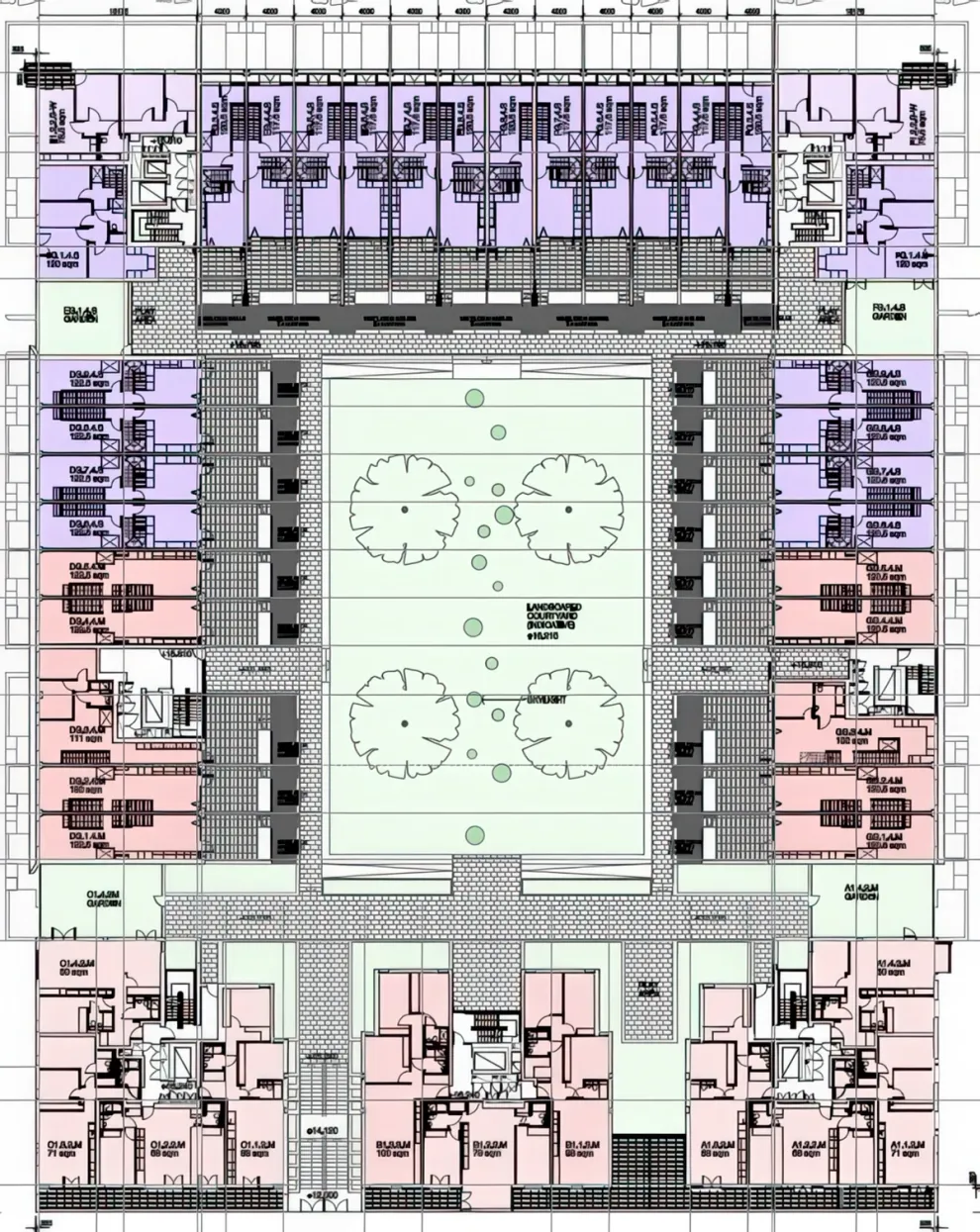

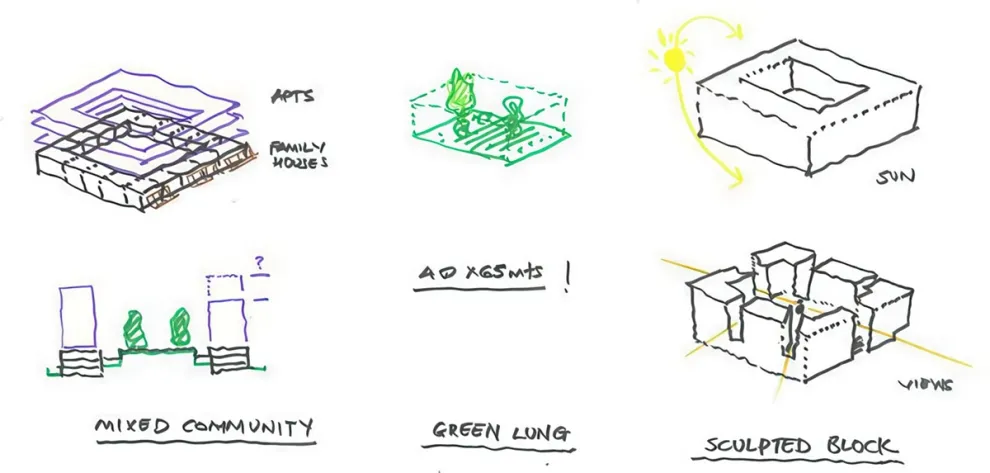

In partnership with London-based architects, Patel Taylor, BVN was engaged by Lendlease to design two of the 15 plots comprising the village. Each plot was a city block, containing 290 apartments across seven buildings arranged around a private courtyard. The initial brief was for a mixture of apartment types and sizes — market-priced, “affordable” for people on middle incomes and a portion for social rent. These would translate to a new neighbourhood after the Games with options for all household sizes and incomes.

For the Games, the apartments were subdivided with temporary partitions to create hotel-style shared rooms supplemented by two large temporary buildings for communal dining and entertainment. Bathrooms were finished to their post Games configuration to minimise legacy refit.

Each building was based on a vertical configuration of three-storey, four bedroom townhouses (also referred to as maisonettes) accessed directly from the street, with seven levels of apartments above. These were supplemented by a mix of single to three-storey shops and offices. The central courtyard tops a single level of basement parking, creating a pedestrianised environment.

Breaks between the buildings combined with different façade types provide identity and variety and allow light and air to flow through to the central courtyard. The breaks are connected by glazed wintergardens that combine with balconies to give residents at every level access to outdoor space.

Host cities have typically involved the private sector in funding and legacy transformation of the village, often underpinned by an urban renewal imperative. London 2012 has taken its place in this evolution, ably demonstrating the conversion of a rundown area of the city into a new sporting and residential park.

There is ongoing debate about the best approach in relation to sustainability and affordable housing so that genuine benefit for the broader community can flow from the athlete’s village. This has extended to reductions in space requirements and minimising waste associated with legacy conversion.

Through its involvement in the Sydney 2000 athlete’s village in Newington, London 2012 East Village and the ongoing development of Sydney Olympic Park, BVN has seen the athlete’s village model evolve and is keen to see sustainability, diversity and urban design play an even greater role in the planning of athlete’s accommodation for Brisbane 2032.

The Process