Opinion — June 10, 2025

Transforming Corporate Campuses: A Road Map to Reinvention

The global shift to remote and hybrid work has fundamentally disrupted our understanding of the workplace. One of the most striking consequences is the growing irrelevance of large corporate campus buildings.

Once the crown jewels of organisational infrastructure, they are now sitting underutilised or, in some cases, nearly empty. This shift has raised a central and pressing question:

How do we reimagine and redefine the role of campus office buildings to ensure they remain relevant today and into the future?

The corporate campus was never just a building. In the United States, early corporate campuses were designed for research scientists and engineers. Inspired by Ivy League universities, they often featured landscaped gardens or grassy quadrangles, creating serene, car-accessible environments. These spaces had a dual purpose; internally, to build a sense of community among employees; externally, to project a carefully curated corporate image.

Architect: Eero Saarinen

Image: Esto/Jeff Goldberg

Over time, the model evolved into a strategy that married culture with commercial real estate. Campus buildings enabled organisations to scale community-building efforts, allowing developers to construct purpose-built facilities that locked in long-term tenants.

This era saw the rise of the 'groundscraper', massive floorplates spread horizontally to maximise connectivity, based on the idea that horizontal expansion fostered better collaboration than vertical high-rises.

Australia has led the global campus movement for the past two decades. From the early 2000s, bespoke campus developments were viewed as the pinnacle of commercial workplace design. These buildings typically featured large open floorplates, central atriums, interconnecting stairs, and integrated services. They embodied a cutting-edge workplace strategy, where evolving technology enabled more flexible work settings and diverse modes of working.

Campuses also supported urban regeneration. Many were built on former industrial sites just outside the CBD in areas not quite central enough to charge CBD rents, but close enough to benefit from proximity. The campus model helped reposition these areas, especially docklands and fringe districts, as vibrant commercial precincts. However, employers needed to offer more amenities, better design, and a stronger sense of identity to attract top talent to non-CBD locations.

Notably, these campuses became early adopters of ambitious sustainability goals, often setting global benchmarks. Their scale and purpose offered a unique opportunity to take a more holistic approach to workplace design.

As a result, they attracted some of the world’s most visionary architects and designers.

Despite their design excellence, many of these buildings are only halfway through their first life cycle, and their relevance is already being questioned. The rise of hybrid work has reduced demand for centralised office space. Meanwhile, the precincts surrounding these campuses have experienced uneven outcomes. Some have matured into thriving hubs; others have stagnated or stalled altogether. Long-term leases are now approaching expiry, prompting critical decisions about renewal, repurposing, or reinvention.

One of the fundamental issues lies in the self-sufficiency of the campus model. These buildings were designed to be inward-facing where everything employees needed was provided within the walls. But this internalisation has come at the expense of the surrounding neighbourhood. By drawing life and activity inward, many campuses failed to support street-level vitality or allow an urban ecosystem to grow around them.

In some areas, clustering campus-style buildings without integrated cultural or mixed-use elements has resulted in monocultures. These precincts functioned well when their anchor tenants thrived, but they quickly hollowed out when disrupted (as with the rise of hybrid work).

Cities that leaned too heavily on this model now grapple with the consequences. A lack of long-term thinking, combined with the assumption that commercial growth would be perpetual, has exposed these areas.

Around 40% of Australia’s commercial building stock is over 30 years old, meaning any significant refurbishment often falls into the category of adaptive reuse - a process that is typically more complex and harder to make financially viable.

In contrast, we’re sitting on a large inventory of campus-style office assets just 10–20 years old, barely halfway through their first lifecycle. These buildings were often high-quality, world-class developments when first constructed, and many still are. With limited new commercial builds on the horizon, revitalising these relatively young assets represents a far more compelling financial and strategic proposition.

So, how do we make campus buildings relevant again?

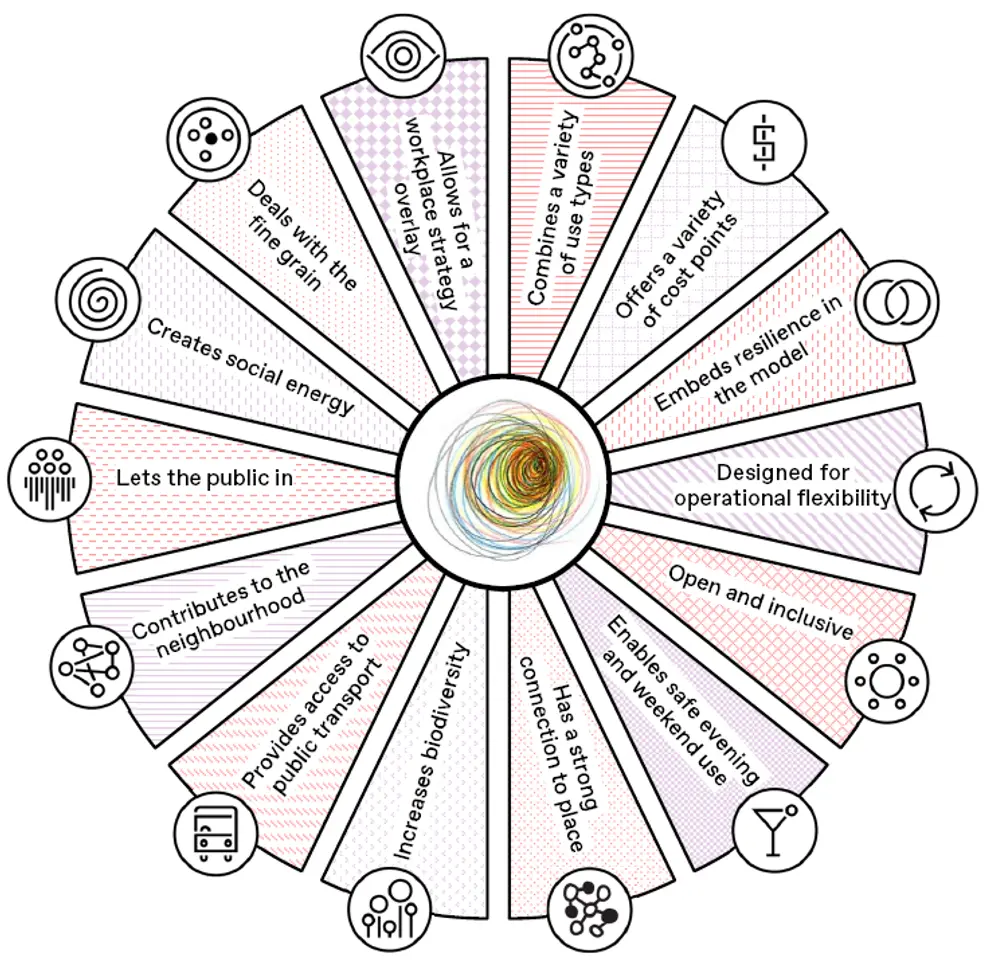

The following framework outlines key ingredients that, in our view, define a successful modern campus. While there are many variables, these five are critical to long-term relevance and resilience.

What role does the building play in the wider neighbourhood?

Historically, many campus buildings were inward-facing and self-contained, designed for efficiency and security, but not integration. To remain relevant, campuses must shift from isolated enclaves to open, welcoming spaces that connect with their surroundings.

Key question: Can these once-impermeable campuses be opened with cross-site links, public access, and active edges that encourage local engagement?

Resilience must be designed in, financially, socially, and spatially.

This means creating a mix of use types at varied price points. A diverse ecosystem of tenants and activities makes for a more dynamic, flexible campus and prevents overreliance on a single group or function.

A common pitfall is the urge to monetise every square metre. Instead, additional uses like retail, hospitality, or cultural elements should be seen as attractors, not just revenue streams.

If there's an anchor tenant, surround them with short-term, complementary tenants such as startups, research groups, and creatives who want to be near the core. This is the premise behind successful innovation districts — critical mass draws others in and creates momentum.

The flip side: If you’re the anchor and innovation is your goal, the environment around you matters. The campus shouldn’t just be an administrative hub; it should be a generator of energy, ideas, and collaboration.

Your campus is a physical manifestation of your brand and how you appear.

While many campus buildings have led the way in sustainability and workplace innovation, they’ve often done so without deeply engaging with society or community. Designed pre-hybrid, for good reasons at the time, many now feel disconnected from their urban context.

A modern campus should reflect operational excellence, purpose, values, and social connection. It should physically and symbolically break down the boundary between inside and out.

Campuses that feel closed off or polarising reinforce public scepticism about big institutions. But campuses that are open, human-scaled, and inclusive can help reshape trust and engagement.

People increasingly want to be part of something that stands for more. A campus with a strong, visible sense of purpose and brand will attract like-minded individuals.

Old models assumed people would work the same way, at the same time, in large groups. But today, we need diverse, flexible, human-centred environments.

Great campuses now need to offer a variety of settings; spaces to gather, focus, and be alone but feel connected. They need to deliver something you can’t get working from home.

Ultimately, the most successful campuses will be those that understand and support what it means to be human: spaces for connection, autonomy, belonging, retreat, contemplation and collaboration.

These buildings are not at the end of their life, but some are flatlining. Strategic intervention now, whether through design, policy, leasing, or placemaking, can give them renewed relevance and longevity.

Sometimes, a few bold moves may be enough to shift the trajectory.

Revitalising our campus buildings isn’t just a clever use of existing resources, it’s an opportunity to redefine the future of work, community, and urban life.

Campus buildings are uniquely positioned to lead because of their size and singular ownership. They can pilot new ideas, set new standards, and scale positive impact quickly through sustainability, community partnerships, or workplace innovation.

Ultimately, the transformation of corporate campuses is more than a design or leasing issue, it’s a layered urban, economic, and cultural challenge. Reimagining these spaces will require new models of placemaking, deeper integration with communities, and a willingness to rethink how we define the workplace.

A plausible place to start is to ask; Can our Campus be turned inside-out? Can we build in more diversity? Can we find alignment with our Brand? Can we make it more human? Do we have a case for reinvention?